What good is an ecosystem? Or rather, what goods are an ecosystem? Clean water and air, climate regulation, flood and erosion management, biodiversity and on and on. Can we value just one enough to get the rest for free? Should we put a price on each one and sell them separately? Or is that like taking a fresh-from-the-oven pizza and selling the cheese and toppings to different customers?!

Smart land managers and potential biodiversity market participants alike know that creating multiple revenue streams is often the difference between financial viability and bankruptcy. A forest manager can sell hunting access to the same land they sell timber from, or may sell some of the land’s development value later on. A restored hectare of land with excellent biodiversity outcomes can sell biodiversity credits, but may also have carbon credit value. Emerging biodiversity markets will inevitably coexist and compete with other nature markets and ‘registered’ credits, including voluntary carbon markets, water quality trading and others, with their own rules, jargon, and registries.

The conversation around how to generate multiple revenues from ecosystem credits is continuously evolving. The most straightforward way thus far seems to be to generate different ecosystem services (units or credits) from different, discrete supply areas of a project site. But what happens when you want to generate more than one credit from the same supply area of the property? Do you bundle? Do you stack? The debate goes on; stacking, bundling, or other terms have their champions and critics. What’s risky, what’s theoretical or unproven, and what’s the best way forward? How do we find the beetle in the pay stack?

Here we’ll have a crack at untangling how bundling and stacking fit into the growing biodiversity credit market using examples from the US and UK, which serve as an interesting contrast between long-established markets and an emerging nature market landscape.

“There are only two ways to make money in business: bundling and unbundling”

— Jim Barksdale, ex-CEO of Netscape and AOL

Clarity on Definitions

The terms bundling and stacking are raised quite frequently. Not surprisingly, there are differences in how the terms are interpreted and applied and nuances around whether ecosystem functions or services are sold together or separately. The Business and Biodiversity Offsets Program (BBOP 2018) provides a deeper dive into the bundling and stacking approaches that have been attempted globally, highlighting how additionality, ecological complexities, and transaction costs have largely prevented some stacking approaches from developing in practice. Finding a general consensus on the basic terms can refocus the conversation to help ensure that emerging approaches in biodiversity markets avoid “double-counting” (aka “double-dipping” or selling the same outcome twice) and lead to genuine outcomes for biodiversity.

First, what is bundling and stacking?

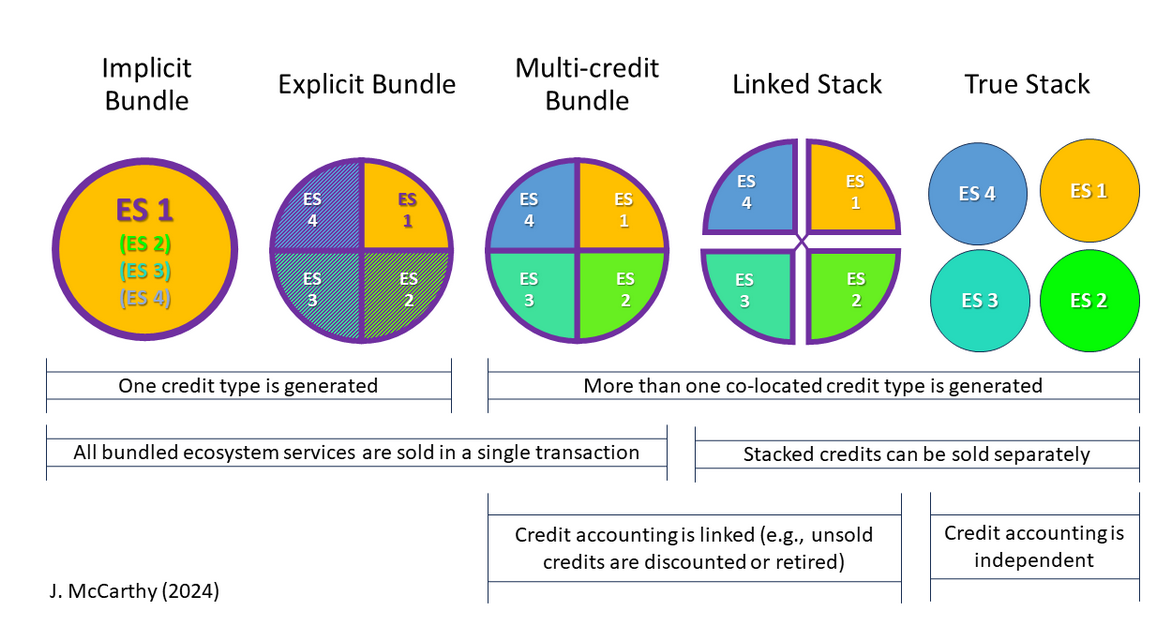

“Bundling refers to when more than one ecosystem service produced on a piece of land is sold as a single trade or credit to a single buyer.” (IEMA 2023) A bundle may represent multiple overlapping co-benefits within a supply area, and the level of quantification of each discrete function/service can vary. For example, an implicit bundle represents multiple, overlapping functions/services that are not individually quantified or measured, whereas an explicit bundle defines and measures functions/services more explicitly, and thus may more closely resemble a stack (BBOP 2018). Arguably, when the biodiversity benefits of carbon credits (or other credits) are implied, e.g., through marketing with images of nature or descriptions of biodiversity, this should be considered an implicit bundle, as the implied biodiversity value affects both sales volume and price.

“Stacking is when various overlapping ecosystem services produced on a given piece of land are measured and separately ‘packaged’ into a range of different credit types or units of trade that together form a stack.” (BBOP 2018). A prerequisite to stacking is ecosystem unbundling, or representing an ecosystem as its discrete and divisible functions and/or services, which can be particularly challenging when it comes to interlinked functions or services (Robertson et al. 2014).

Is it really that simple? Well, no.

As we dive in further, the lines seem to blur, and what is emerging in practice does not always fit neatly into the boxes of a bundle or a stack. The variability in practice can be distilled into 1) whether ecosystem services are defined as separate credits, 2) whether those credits can be sold separately, and 3) whether stacked ecosystem services are unbundled and accounted for independently.

On one side of the spectrum lies implicit and explicit bundling, where there are co-benefits, but only one credit type is generated and sold. Another form of bundling can occur where an area/activity may generate more than one credit type (meeting the criteria to generate units in each respective credit type), but the credits are bundled for purchase, and sold only once to a single buyer. For example, a site may generate a bundled Salmonid/Riverine Riparian credit that can be sold to meet wetland offset requirements, species offset requirements, or a combination, but only in a single transaction. This type of multi-credit bundle (sometimes referred to as ‘Stacking without unbundling’) occurs when multiple credits form a stack, but they cannot be sold independently. In this scenario, you could generate both carbon and biodiversity credits, allowing the sale of multiple types of credit, but any credits could only be sold under a single, bundled transaction. Effectively, the ecosystem value of the supply area is kept whole, avoiding the risks and complexities around ecosystem unbundling.

Moving along the spectrum is a form of stacking where multiple credits form a stack, these credits can be sold in more than one transaction (or to more than one buyer), but the credits are linked (i.e, not accounted for independently). For example, in US water quality trading, this is referred to as ‘proportional accounting’, and occurs when more than one credit type is defined and sold, but the remaining credits in the stack are discounted or retired following a transaction. Say 50% of one credit type from a supply area is purchased in a transaction, then the remaining available credit types would all be discounted by 50% for subsequent transactions. In this case, co-located credits can be sold to multiple buyers, or in more than one transaction, but this depends on availability of remaining credits. Because the credit accounting among credit types is linked, this type of approach also reduces the risk of selling interlinked functions/services more than once.

On the far side of the spectrum lies the concept of true stacking (or “payment stacking” or “stacking with unbundling” or “unstacking”), where separate payments can be received for each type of credit. Hypothetically, with true stacking, you could generate carbon and biodiversity credits from the same activity, and then sell them to separate buyers and/or accept payments for separate impacts. This type of stacking remains relatively rare in practice, likely due to policy restrictions, complex additionality criteria, transaction costs and the practical risks and challenges of ecosystem unbundling and disaggregating linked ecosystem functions/services (BBOP 2018).

Status Quo in the US and UK

In the US, the primary biodiversity-related ecosystem markets generally allow for ‘bundling’ and some types of stacking, but they draw the line at ‘true stacking.’ Clean Water Act (CWA) regulations allow for stream/wetland mitigation projects to be “designed to holistically address requirements under multiple programs and authorities for the same activity.” As such, joint banks have been developed which sell co-located wetland/stream mitigation credits (CWA) and conservation/species credits (Endangered Species Act), and, where agreed, these compensatory mitigation credits can also be sold to meet requirements under water quality or nutrient trading programs as well. However, the CWA regulations mentioned above are also quite clear that credits can only be sold to offset one impact. In other words, credits (e.g., ESA and stream/wetland credits) can be sold to a project needing to offset impacts to one or more resources, but these credits cannot be unbundled and sold separately for two different projects (e.g., for ESA/wetland impacts of one project and then again for water quality later). For a rundown of the updated rules in species markets, see Becca Madsen’s (of EPIC) blog here. There are also examples from water quality trading programs, where the sale of one credit type results in a proportional reduction of credits from other co-located credit types (e.g., the Willamette Partnership General Crediting Protocol), although specific policies vary state-to-state. But in practice, co-located credits are generally either sold in a multi-credit bundle or a linked stack, where unsold stacked credits are discounted or retired after a single transaction. Note that compatible uses that could generate payments for landowners, such as duck hunting, can be approved at a bank site but this is not considered a form of stacking.

To date, we aren’t aware of examples in the US where true stacking approaches have been allowed or implemented within biodiversity-related credit markets or where stacked services/functions are inextricably connected. However, there are other market-based approaches that stack multiple ecosystem services but sit outside the construct of ‘registered’ credit markets. For example, bi-lateral trading models exist where landowners are paid for the services generated and the resulting gains are used to meet insetting requirements, risk reduction targets, etc. An example of this type of approach is the Soil and Water Outcomes Fund, where they provide the landowner a combined ecosystem service payment for all benefits produced, and use the resulting gains towards carbon sequestration and water quality insetting requirements of market participants (note that biodiversity is not explicitly identified as a co-benefit). While this seems to fall within the definition of bundling (i.e, all ecosystem benefits are purchased together in a single transaction), it also seems to allow for the unbundling of these benefits in subsequent transactions between the intermediary and market participant. Further discussion of these market approaches is outside the scope of this blog, but it should be noted that the same double-dipping issues can arise and transparency is needed.

Unlike in the US, where the primary markets have drawn a clear line on whether they allow ‘true stacking’, the direction of emerging markets in the UK is less clear. As England kicks off their ambitious Biodiversity Net Gain policy, new guidance has been released allowing for stacking across BNG and nutrient markets (provided eligibility criteria are met for each market). The guidance defines stacking as selling multiple credits or units from different nature markets separately from the same activity on a piece of land – a definition which appears to leave the door open to a range of stacking approaches, including ‘true stacking’ models. The guidance also discusses how BNG and nutrient mitigation could align with voluntary carbon credits or the use of other environmental payments on the same land, although this does not appear to be considered stacking. Emerging voluntary biodiversity markets in the UK sometimes also allow for stacking. For example, PlanVivo notes that biodiversity credits can be stacked with carbon (assuming additionality criteria are met), but only with approved carbon codes, which to date includes only the PlanVivo Carbon Standard.

Recently, the British Standards Institute put out a new “flex standard” for nature markets for consultation, with definitions of bundling and stacking that generally align with the ones above. This standard also appears to leave the door open to a range of stacking approaches, so long as there is “robust measurement and verification of additionality in place for each type of unit in the stack.” The flex standard also specifically addresses double-counting, with requirements that are intended to build on additionality and bundling/stacking trading rules – it’s possible these requirements could serve as guardrails to prevent the unbundling and separate sale of interlinked ecosystem functions/services. However, it’s still unclear in both the UK compliance and voluntary biodiversity markets how well eligibility, additionality criteria and requirements on double-counting will address ecological complexities, and whether there will be clear limits on how stacked credits can be sold, as we’ve seen in the established markets in the US.

Charting a low-risk path forward

Whatever bundling and stacking models emerge in nascent biodiversity markets in the next few years, it’s important to remember the overarching goal that high-integrity markets are aiming for – that these markets result in measurable, additional outcomes for biodiversity, above all else. Biodiversity represents the variability among living organisms and the ecological complexes of which they are a part. This requires thinking about the whole ecosystem in how we market and sell biodiversity gains, and whether it’s appropriate (or feasible) to unbundle biodiversity from its supporting and interconnected ecosystem functions/services. Arguably, robust additionality criteria can go a long way towards preventing double-dipping. But can we rely on financial and legal criteria to do this? How do we tackle the ecological complexities of biodiversity and ensure that interlinked functions/services are not sold more than once to separate buyers? Can a biodiversity outcome be disaggregated clearly enough to sell it as a truly separate commodity? Should it be attempted?

Here are four recommendations to make bundling and stacking less of a risk:

-

There needs to be clear guardrails and governance mechanisms in place to prevent double-dipping. For example, in implicit bundles, we need to ensure that biodiversity credits are not subsequently sold from a property on which nature benefits have already been marketed to a different type of credit buyer. And in stacking, we need to acknowledge that ecosystem unbundling has its limits – interlinked functions should not be unbundled and sold to separate buyers.

-

There needs to be transparency in credit accounting that allows for credit integrity evaluation. Credit sellers, methodology developers, and registries need to be specific about what they’re doing, and this information needs to be clear and understandable. It should not take an investigative journalist or an exhaustive technical review to uncover the details of how credits are generated, marketed, and sold.

-

When buyers are engaging in markets as a way to address their impacts, whether in compliance offset markets or through voluntary markets, the equivalence of impacts and uplift needs to be considered – the same ecosystem services/functions need to be accounted for on each side of the equation. Buyers need – and regulators or equivalent project validators must require – absolute clarity on when selling stacked credits to different buyers is appropriate, and whether re-selling of unbundled credits is allowable. Let’s not let vague guidance create a policy gap.

-

Emerging biodiversity markets, and especially voluntary markets, should aim for simplicity and legibility, recognizing that attempts at bundling or stacking may add layers of risk and complexity. Early transactions will work out better if complex additionality determinations or ecosystem accounting approaches aren’t necessary. There is value in building from established practice elsewhere with well-considered pilots of new approaches, and within new markets.

As with so many other debates in the biodiversity crediting world, the hard-earned lessons of existing markets – habitat mitigation and species banking, wetlands, carbon, and others – give us the tools for success. Let’s not ignore them.

Julia McCarthy is a research associate at Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC), funded in part by the Scottish Government’s Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division (RESAS) Natural Capital – Galvanising Change (D5.3) project. She is also self-employed as an ecologist (McCarthy Ecology) working with multidisciplinary teams to provide strategic and expert advice to improve environmental program governance, implementation and policy, and advance science-based approaches.

Ryan Sarsfield is the Senior Advisor for Biodiversity Markets at the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC), working to build a market for biodiversity credits in the U.S. and abroad.

This article was originally published on the Environmental Policy Innovation Center blog.