Many companies emit carbon dioxide in the course of their normal business. The amount emitted may differ — an airline or fossil fuel-based energy producer will emit much more carbon than a textile manufacturer.

To offset those emissions, some companies purchase carbon credits through brokers or exchanges. Those credits are meant to fund projects that reduce or capture pollutants.

Companies can also buy credits from project developers. Forestry projects are common, since trees capture carbon during photosynthesis. Projects might aim to preserve a swath of trees from destruction, or plant new ones. The forests saved or replenished can be anywhere in the world.

Companies buy carbon credits for various reasons. They are often the cornerstone of company public relations statements that they are carbon neutral, or they have “net zero” greenhouse gas emissions.

A big question for journalists investigating the growing voluntary carbon market is whether claims of carbon neutrality are true.

Companies don’t necessarily have to buy offsets to help the environment. They can reduce emissions produced by one part of their business to make up for other parts where they can’t reduce them.

But changing business processes to reduce emissions can be difficult.

That’s a big reason why offsets are so commonly used in carbon neutrality claims. According to a 2021 study of such pledges from 35 large global firms, 66% of them used carbon offsets.

Another wrinkle in carbon neutrality claims: Products companies make may produce pollutants when consumers or other businesses use them. In gas fuel production, for example, there is carbon emitted to refine gas, and carbon emitted to make the energy that powers the refinery.

Then there is the carbon emitted when someone burns the fuel to drive their car. For firms working in those industries, more than 90% of greenhouse gas emissions don’t come from the company itself, according to the 2021 study, from the Columbia Center on Sustainable Development.

The growing voluntary carbon market

Though many companies purchase carbon offsets voluntarily there are two U.S. states, California and Washington, which regulate their biggest polluters using market mechanisms. Most states in the northeastern U.S. have binding regulations that do the same, but they focus on energy producers.

The voluntary market, valued at about $2 billion in 2020, could be worth $250 billion by 2025, according to a 2023 research memo from investment bank Morgan Stanley.

Companies access vital information about offset markets through registries, which are usually nonprofits. Registries record credit ownership, for example. Registries also have protocols, or rules, on how projects measure their carbon reductions. Protocols are meant to ensure carbon offsetting projects produce the environmental benefits claimed.

While records in states that regulate carbon emissions are likely to be subject to public record laws, records for voluntary carbon offsets are not. But the major registries make some data public.

Another question for journalists to ask is whether a carbon-saving project would have happened anyway without carbon credits being purchased.

Did carbon credits save that forest? Or was that forest in no danger of being cut down?

A major challenge in reporting on carbon offsets is disparate sources offer data in various formats — registries may use different phrases to note that a carbon credit has been issued, for example.

Those differences make market-wide analyses difficult and time consuming.

OffsetsDB from CarbonPlan

Enter OffsetsDB, a navigable and standardized repository of carbon offset data from five of the biggest registries operating in the voluntary carbon offset market: American Carbon Registry, ART TREES, Climate Action Reserve, Gold Standard and Verra.

The free tool is updated daily and produced by CarbonPlan, a nonprofit open data organization focusing on climate change solutions. Anyone can download the data and access documentation for carbon offset projects around the world.

To help journalists understand the offset market and get to know OffsetsDB, we recently hosted an hourlong webinar featuring Grayson Badgley, a research scientist at CarbonPlan, and longtime science journalist Maggie Koerth, editorial lead at CarbonPlan.

“I really genuinely believe that at the core of just about every single project there’s this nugget of truth,” Badgley said during the webinar. “There is this good thing that is happening. The real question is, is it being credited appropriately?”

Watch the video to learn more — and read four takeaways from the presentation and conversation.

1. Know these key terms before digging into offset data.

There are lots of specialized words and phrases in the world of carbon offsets.

Here are a few you need to know.

Additionality: This refers to whether a carbon-saving or carbon-reducing project funded by carbon credits is adding environmental benefits that couldn’t have existed without the credits.

credit: A credit is a financial instrument that represents carbon-removing activities. Credits are often created by projects that remove carbon from the atmosphere, such as reforestation, or prevent it from reaching the atmosphere, such as landfills that capture and burn methane.

“Many [companies] buy credits,” Koerth said. “And that is, somebody else does the carbon removing activity and then sells the company the right to claim that removed carbon.”

Offsets: Credits become offsets when a company or other entity makes a claim, such as carbon neutrality, based on the credits they’ve purchased. The company is claiming that their carbon emitting activities are offset by the credits.

“The terms credit and offset are kind of used interchangeably because the majority of credits are ultimately used to make offsetting claims,” Koerth said.

Registry: A registry is an organization, typically a nonprofit, that tracks carbon credit markets, including the buying and selling, issuance and retirement of carbon credits.

“[Registries] keep a record of all the credits produced by a project when they’re sold, when the sold credits have officially been used,” Koerth said. “Basically, this whole system of the registries exists so that the same credits can’t be sold multiple times to different people.”

Issuance: When a credit has been created, registered, and a registry confirms it exists, the registry issues the credit.

Purchase: When a credit is bought, typically by companies seeking to offset their carbon-producing activities. While credit issuances and retirements are publicly available, purchase information is usually not public.

Retirement: When the buyer of a credit declares they have used the credit and put it toward an offsetting goal, the credit is retired. Retired credits can’t be used again.

Vintage: This is the year a carbon credit was created.

Carbon neutral or net zero: These are claims companies make that their carbon emissions are balanced, for example, by buying credits. Say a small coal plant emits 900 million metric tons of carbon each year. It then buys credits equaling 900 million metric tons in carbon offsetting activities. On net, the coal plant claims to be neutral in their emissions.

There are many more phrases to know in the world of carbon offsets. The U.K.-based news organization Carbon Brief offers an extensive glossary.

2. Understand additionality.

Additionality is a big word with a big question behind it: Would a carbon sequestration or reduction project have happened anyway without funding from carbon credits?

Journalists need a basic understanding of additionality, a crucial concept that carbon offset projects use to justify their existence.

“In practice, determining whether a proposed project is additional requires comparing it to a hypothetical scenario without revenue from the sale of carbon credits,” according to this explainer on additionality from the nonprofit Stockholm Environment Institute.

In other words, is the sale of carbon credits adding environmental benefits by funding a carbon offsetting project that could not have happened without that funding?

“A lot of this is based around both trying to see what you have done and trying to estimate what would have happened if you hadn’t done that thing,” Koerth said during the webinar.

As Badgley and Freya Chay write in a 2023 analysis for CarbonPlan, “Rather than creating new climate benefits, non-additional credits simply reward a landowner for doing what they already planned on doing.”

While there are no hard and fast rules for determining whether a project is adding carbon benefits, journalists and others can use data in OffsetsDB to identify projects that potentially are not.

Think of a hypothetical landfill. Landfills produce methane, which scientists consider a worse air pollutant than carbon dioxide. But when methane is burned, it turns into carbon dioxide. So the landfill burns methane and receives carbon credits it can sell on the offset market because the carbon it is emitting is not as bad for the environment as methane.

Badgley and Chay recently analyzed 14 such carbon offset landfill projects. If a landfill stops receiving carbon credits to sell, the methane burns at those landfills should drop off or stop — if those projects are adding environmental benefits that wouldn’t be possible without the credits.

That’s not what Badgley and Chay found.

“By comparing crediting data from the Climate Action Reserve with landfill gas collection data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, we found that nearly 50 percent of the credits issued under this protocol are likely non-additional,” they write. “These credits do not represent high-quality outcomes for the climate.”

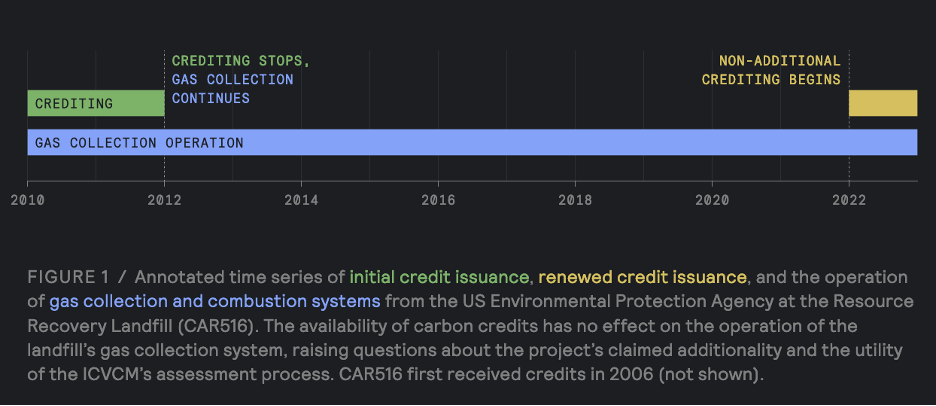

For example, the Resource Recovery Landfill project in Cherryvale, Kansas, received credits from 2006 to 2011 for its gas collection operations, including burning methane, according to the analysis.

In 2012, those credits stopped — the landfill didn’t file paperwork to keep them going, Badgley and Chay found. But the gas collection continued. Crediting began again in 2022. During those 10 years, the landfill’s gas collection didn’t disappear or slow down. It expanded, according to the analysis.

“To be clear, the fact that Resource Recovery’s gas collection system ran continuously is a good thing for the planet,” write Badgley and Chay. “In addition to reducing methane emissions, collecting and treating landfill gas can help reduce smells and other environmental side effects associated with operating a landfill. But offsets must be used to spur new climate action — not just reward existing actions.”

(CarbonPlan)

3. Know that parts of the carbon offset market aren’t disclosed in public registry data — but this information may exist elsewhere.

Offset credit purchases, for example, are not usually public information. Other transaction details are also missing in public data.

For example, OffsetsDB shows that Jaiprakash Hydro Power in India has issued 16.7 million credits and retired nearly 9 million since 2010.

But which entities bought and retired those credits is potentially unavailable.

Sometimes, companies will voluntarily disclose to registries that they have purchased or are retiring credits.

But that doesn’t always happen.

Company sustainability reports are one place to look for information on how many credits a company has retired, and why, Badgley said. A company might, for example, purchase carbon credits to offset executive travel and publicly disclose that for public relations purposes.

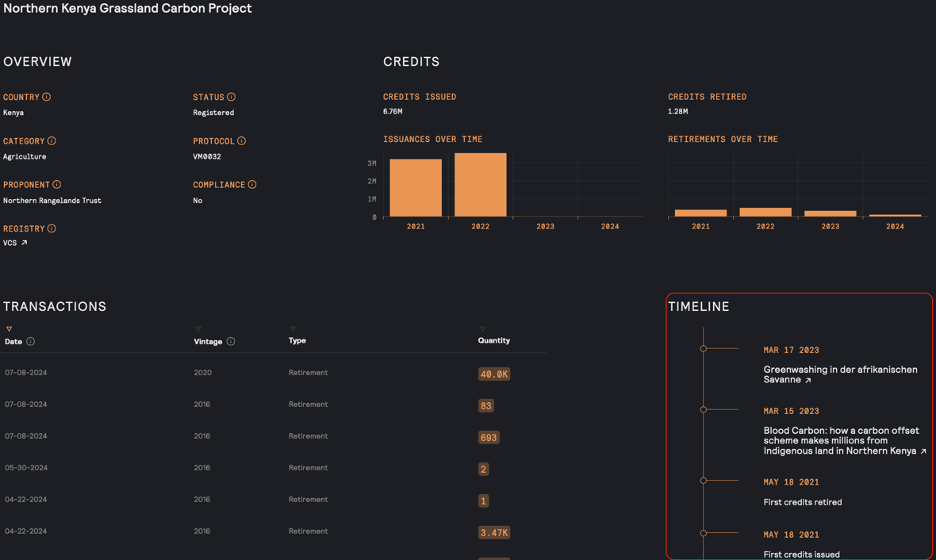

“What we’re hoping to do with OffsetsDB is start to pull in a lot of that information,” Badgley said, adding that it’s a manual process of gathering supplementary knowledge from places like sustainability reports and news articles. This appears as a timeline for individual carbon offset projects within the database.

(CarbonPlan)

Recent legislation passed in California requires that any company marketing or selling carbon credits in the state, or any company buying or selling credits, disclose much more information online.

This includes the type of offset project, where the project is located, whether a third party has verified the project, and more. (But it’s unclear when the law will take effect and how it will be enforced, Politico reports.)

“This is something that we’re really excited about,” Badgley said. “And we’re hoping to be able to sort of pull that paperwork and pull that information into OffsetsDB.”

4. Ask about registry buffer pools.

What happens when a carbon-emitting company buys credits from, say, a forestry project in northern California that later is subsumed by wildfire? The registry that issued the credits will likely dip into its buffer pool to make up for the loss.

A buffer pool is a sort of rainy day fund, made up of carbon credits reserved for emergencies. Usually a carbon offsetting project can’t sell all its credits, but has to put a fraction of them into the registry’s buffer pool, Badgley said.

While the practice “makes total sense,” Badley said, it also raises questions. What types of credits are in the buffer pool? Do replacement credits represent similar offsetting projects to the original ones?

Here’s a relevant question for journalists to ask of registries: “Is this buffer pool that this program is administering, is it designed to make good on the liabilities of the program for the next X years?” Badgley said.

Further reading

Another Forest Offset Project is Burning — If You Know Where to Look

Grayson Badgley. CarbonPlan, July 2024.

The First Offset Credits Approved by a Major Integrity Program Don’t Make the Grade

Grayson Badgley and Freya Chay. CarbonPlan, July 2024.

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Carbon Offsets

Global Investigative Journalism Network. Toby McIntosh, March 2024.

Instead of Carbon Offsets, We Need ‘Contributions’ to Forests

Libby Blanchard, William R.L. Anderegg and Barbara K. Haya. Stanford Social Innovation Review, January 2024.

What Every Leader Needs to Know About Carbon Credits

Varsha Ramesh Walsh and Michael W. Toffel. Harvard Business Review, December 2023.

Glossary: Carbon Brief’s Guide to the Terminology of Carbon Offsets

Daisy Dunne and Josh Gabbatiss. Carbon Brief, September 2023.

In-Depth Q&A: Can ‘Carbon Offsets’ Help to Tackle Climate Change?

Josh Gabbatiss, et. al. Carbon Brief, September 2023.

Action Needed to Make Carbon Offsets From Forest Conservation Work for Climate Change Mitigation

Thales West, et. al. Science, August 2023.

The Voluntary Carbon Market: Climate Finance at an Inflection PointBriefing Paper. World Economic Forum, January 2023.

Corporate Net-Zero Pledges: The Bad and the Ugly

Jack Arnold and Perrine Toledano. Columbia Center on Sustainable Development, November 2021.

Source