AT A GLANCE

• As organizations make carbon-neutral pledges, more are turning to carbon pricing instruments to hedge positions.

• Since their launch in 2021, more than 200,000 carbon offset futures contracts have traded at CME Group, equating to 200 million metric tons of CO2 offsets.

Fixing a price on carbon is the Everest of challenges in the effort to halt the rise in global greenhouse gas emissions.

That’s because imposing a cost on emitting another metric ton of carbon dioxide requires an entire ecosystem of workable and verifiable markets, which includes a range of instruments such as carbon offsets.

The good news is that carbon markets are becoming an indispensable tool in the climate fight. Carbon pricing instruments now cover over 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions, generating $53 billion in revenue at the end of 2021, according to the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition. That represents a 17% increase in revenue from the previous year.

The tough news is that the job of reducing emissions is not an easy one. Collectively, the world spews 50 billion metric tons of CO2 in the atmosphere each year, a 40% increase in emissions since 1990, according to Our World in Data.

Shrinking Carbon Footprints Through Offsets

Companies, while often working to reduce their own emissions, are increasingly turning to carbon offsets, which can be verified by established registries, to shrink their carbon footprint.

A carbon offset credit is a transferable instrument certified by independent entities or governments, and each credit represents a reduction of one metric ton of carbon dioxide, or an equivalent greenhouse gas.

The credits, to be effective, must represent an environmentally sound project that helps to mitigate climate change — such as preserving a forest that was slated to be cleared, or building of a clean energy project to eliminate burning of a fossil fuel. After purchasing a credit, a company can “retire” it to claim a reduction in their own greenhouse gas reduction goals.

Read More About Global Emissions Offset Futures

Some of the offsetting efforts, particularly those that are not independently audited, can come under criticism as greenwashing. Corporations are also increasingly aware of the damage caused to businesses in such cases.

“If you use an offset which isn’t particularly credible, and that is something that emerges,” noted David Kane, partner at Baringa, a UK-based consultancy, “then that will cause reputational damage and the risk of reputational damage is huge and has a high impact.”

After verification, a key challenge in carbon offsetting is how to price the credits, and that’s where spot and futures markets come in. CME Group launched the Global Emissions Offset (GEO) futures contract in 2021 with the aim of making it a global benchmark, giving customers a way to manage risk, and helping in price discovery.

Market Growth in its Infancy?

Interest in the GEO futures contract — each of which represents 1,000 offsets — has grown sharply this year, according to Jessica Masters, director of energy products at CME Group.

The market for emissions contracts is becoming more established, “but ultimately, I think there’s still a lot of room to grow. Obviously, this market is still young.”

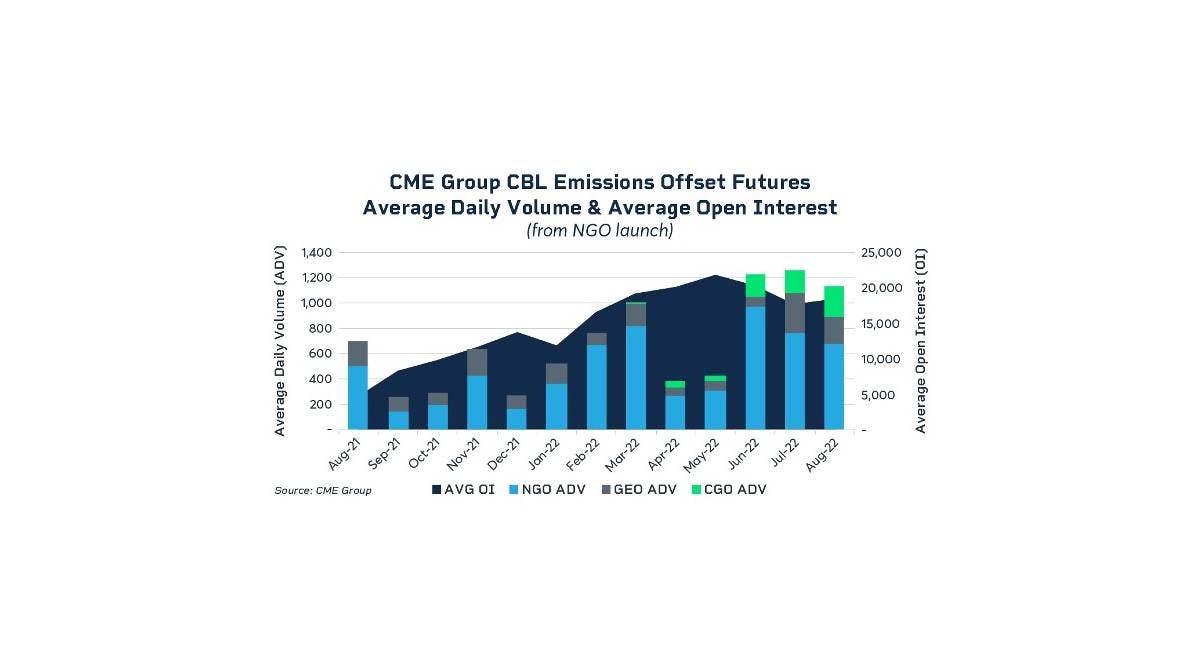

CME Group followed the GEO contract with the launch of Nature-based GEO futures (N-GEO) in 2021 and Core GEO futures (C-GEO) in 2022. All three products have shown growth in trading volume this year.

Total trading volume among the three contracts combined recently reached over 200,000, equating to 200 million metric tons of CO2 offsets. In July of this year, trading hit a record, with an average of 1,200 lots traded daily in the month. The exchange set a single-day record in mid-June when over 5,100 offset futures traded. Open interest, the number of outstanding contracts, exceeded 18,000 in the later months of 2022.

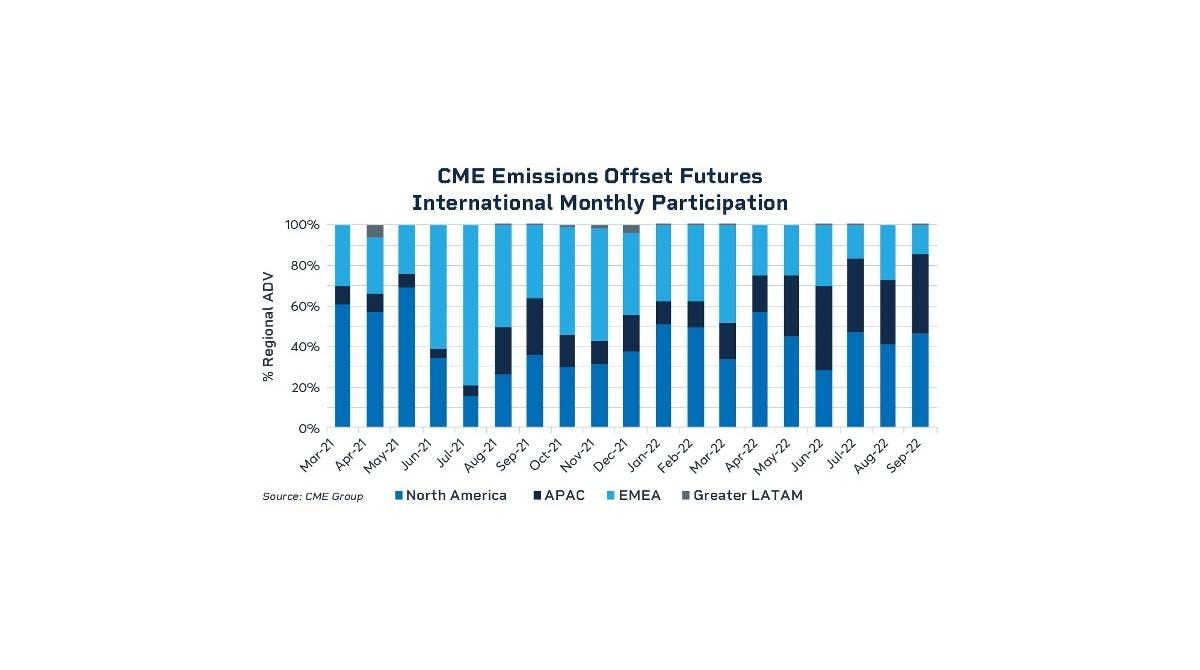

Some 100 different companies have traded an emissions offset futures contract, but, tellingly, more than half of those firms began trading the contracts this year, according to CME Group data.

“We are seeing more and more people enter the carbon markets and all the big commodity traders have established carbon desks, are establishing carbon desks, or are at least analyzing where to place their chips,” said Kane at Baringa.

As a sign of the growing maturity, carbon markets are also attracting speculators, which help to grease the wheels of a growing market. “They play an important role, and help make a liquid market,” Masters said.

Another challenge, however, for the broader market is the differing standards for the array of companies involved in carbon offsetting.

“Everyone will calculate their exposure to carbon a bit differently and that’s a bit of a challenge,” said Kane. “There’s not necessarily industry standards that people can say ‘here’s how I calculate my carbon exposure.’ Therefore, when it comes to offsetting and potentially proprietary trading around that position, it becomes more difficult.”

Pricing Offsets

Pricing is key for market-based offsets. Companies involved in carbon markets need to know whether they are getting bang for their investment buck. And that only happens through price discovery and the establishment of benchmarks — which are crucial in every commodity market, from crude to corn.

“There would be a lot more hesitancy to participate in the market if you had no idea whether what you’re doing is financially sound,” said Masters. “And having a benchmark lends to transparency and provides people with the ability to make strategic business decisions.”

Kane agrees, and says any increase in liquidity will “lead to price discovery, benchmark pricing, and the opportunity to have both secure, credible offsets, and the ability to hedge your emissions position or take directional views in the market.”

In the end, he says, any effective offsets market must help organizations reach their carbon neutral goals.

“Ultimately, all of this has to make a real-world difference to reducing emissions. It’s going to be one of the biggest challenges that these businesses will face in the coming years.”