The concept may seem simple, but it comes with risks and unaddressed questions, experts say. There are ongoing efforts to create the rules for such projects. More details could emerge later this year, or early next.

Corporate carbon offsetting has for decades funded projects in forest management, delivering clean-burning cookstoves to rural communities, and building renewable power infrastructure.

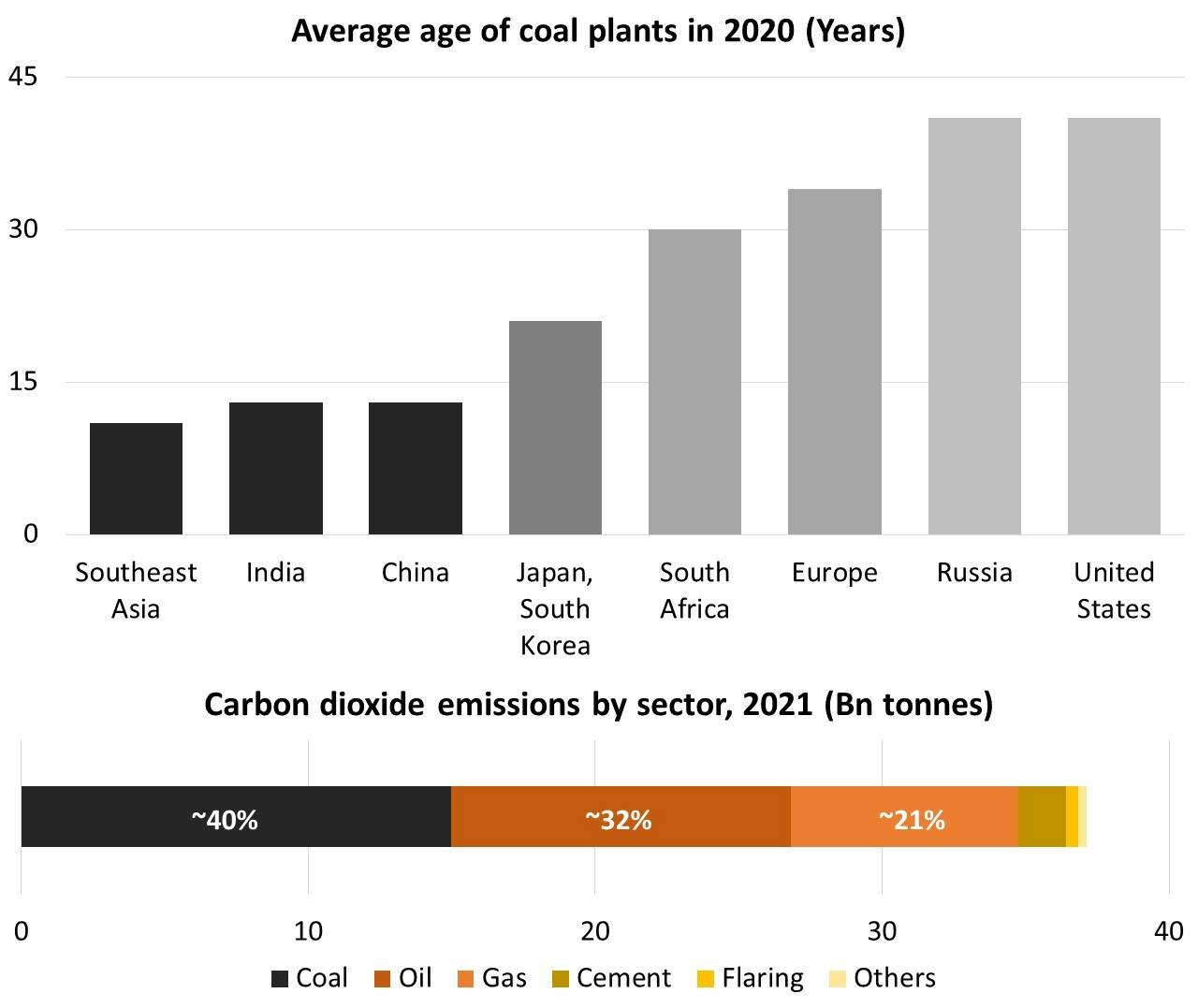

Despite these efforts, the world has continued to heat up steadily towards the 1.5°C safety limit for global warming. Market players are now looking to bring carbon markets to bear on one of the biggest contributors to climate change – coal power plants, especially the newer facilities.

Asia’s huge coal fleet is on average 13 years young. If allowed to run to their full 40-odd years lifespan, these units would spew hundreds of billions of tonnes of carbon emissions and seriously dent climate mitigation efforts.

Resourcing financial packages to close coal power generators has proven especially challenging, even as investors are increasingly likely to shun new coal builds.

Carbon credits, each representing a tonne of emissions avoided, could offer a new revenue stream for retirement projects. Instead of monetary returns, funders get the licence to claim progress on their own corporate net-zero pledges. Last month, the US$130 trillion Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) climate group gave the concept a bump, when it said in a consultation paper that carbon credits could help fund coal retirement in Asia Pacific.

But experts also warn that the sheer scale and complexity of the endeavour means that there is no guarantee that it will work. Initiatives to convert ideas into implementable plans are still in their early stages, while many tough questions remain unanswered.

Needed money

Southeast Asia has some of the youngest coal plants, for which putting together an early retirement deal is particularly difficult. Coal is the biggest contributor to global emissions. Data: IEA, Our World in Data.

Asia’s coal phaseout needs repayment-free funding, such as grants and carbon credits, said Agus Sari, chief executive of Indonesian sustainability advisory firm Landscape Indonesia.

“Retirement of coal power plants does not make money, it increases costs,” Sari said. “[If] you have to finance a losing business with loans and equity, how would you pay back the loan, or provide the return on equity?”

He added that carbon credits could present a “straightforward” funding model and is a good way to mobilise private finance, compared to grants which mainly come from public funding or philanthropy.

Grant money, meanwhile, has been hard to come by for Indonesia, even in the landmark US$20 billion “Just Energy Transition partnership” (JET-P) deal the country signed with developed countries and financial groups last November, Sari noted.

Indonesia, the fourth most populous country in the world, uses coal to generate 60 per cent of its power. The country has been the de facto focal point for the global community on early coal phaseout.

Existing efforts have focused on blended and concessional finance – where multilateral banks, countries, investors and donors pitch in money together to lower project risk and corresponding interest rates. The Asian Development Bank is looking to retire a 600-megawatt coal plant in West Java 10 to 15 years early through a refinancing deal worth up to US$300 million, to avoid up to 30 million tonnes of emissions.

A 2022 study had put the cost of retiring Indonesia’s coal plants by 2040 at US$37 billion. However, an Indonesian minister has put a US$600 billion figure on achieving coal phase-out, according to Bloomberg news.

“Carbon credits, or any other forms of international compensation, for avoiding emissions from coal power plants’ early retirement would make the whole concept worth doing. Otherwise it will be just to force Indonesia to take on more debt and [achieve] nothing much more than that,” Sari said.

There is also the worry that existing efforts won’t be fast enough.

“There is so much happening in [the coal phaseout] space. And yet, there is not one example yet of a transaction of an accelerated coal retirement and replacement with clean power,” said Dr Joseph Curtin, managing director of the power and climate team at The Rockefeller Foundation, a United States nonprofit.

“You’re going to need additional capital from sources such as carbon credits, which can provide a grant-like tranche in the capital stack. That could be the key to unlocking other sources of capital, and mobilising capital waiting to be deployed,” Curtin said.

Curtin is part of the team at the Coal to Clean Credits Initiative (CCCI), a project led by The Rockefeller Foundation and another US-based nonprofit, the Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet. The consortium is writing up rules – envisioned as “a global benchmark” – on how project developers can generate carbon credits from retiring coal plants and replacing them with new clean energy capacity.

CCCI was unveiled in mid-June, and has not made its early drafts public beyond its own consultation sessions. It is focusing on Indonesia, South Africa and Vietnam – the first three countries to sign JET-P deals with foreign funders. Indonesia’s JET-P secretariat has said it welcomes the initiative.

Switzerland-based carbon project certifier Gold Standard is also working on a similar methodology, and had an early concept published for public review in March this year. A more detailed methodology could be ready by the first quarter of 2024, the certifier’s chief technical officer Owen Hewlett told Eco-Business. CCCI plans to present its own work at the COP28 global climate summit at the end of this year.

There is also the United States’ Energy Transition Accelerator programme announced at COP27 last year, which envisions the use of carbon credits. However, that scheme is expected to operate at a higher jurisdictional level.

Big effort, complex questions

Though broadly similar in concept, a coal phaseout carbon project could in many ways look markedly different from other carbon-reduction ventures on the market today.

Firstly, coal retirement will most likely be a two-in-one effort – of subtracting coal and adding clean energy capacity – when most developers today are mostly familiar with projects dealing only with the latter.

Coal power plants are also much more intricately entwined with national development and security than for instance a forest reserve, given coal’s reliability in providing baseload electricity to the masses. Several countries in Southeast Asia have strong state control in the power market to protect power generators from competition and provide affordable electricity to its population.

It all means that a lot more stakeholders, and new ones, will need to be involved.

“I am not sure there is a conveyor belt of developers that are just ready to go, and I am not sure they necessarily look like the traditional kind of developers in carbon markets,” Hewlett said, adding that initiatives would likely be undertaken by consortiums involving host country governments.

And since carbon markets are known to harbour black sheep developers who game the system, rules will need to be watertight.

GFANZ’s consultation paper highlights some potential loopholes. For example, coal plants that would already be shuttering early, perhaps due to heavy carbon taxes or competition from cheap renewables, should not get unnecessary extra funding. The retirement of one coal plant should not cause another to pop up elsewhere – the safeguard being to build new clean energy capacity. CCCI also intends to operate only where governments have commitments for no new coal plants.

Translating such principles into feasible rules will be challenging.

Using renewable energy to compensate for coal could mean having to upgrade electricity grids to withstand variable power input in many parts of Asia. Wind and solar installations will need to be built to higher capacities than the coal plant they are replacing, since such renewables are at the mercy of changing weather conditions.

So the eventual methodologies will need to somehow make sure project developers make good on installing renewables before carbon credits are dished out, but also have “balancing safeguards” when developers face genuine problems, Gold Standard’s Hewlett said.

CCCI acknowledges that the clean power replacement could be partial, and Curtin said the consortium may allow project developers to use other aspects, like grid emission factors, in calculating carbon savings. What exactly counts as clean power is still being finalised, but natural gas will not be regarded as such.

Gold Standard also wants to use emissions factors of best-in-class coal units to calculate baselines, so that plant operators cannot purposely fire their boilers inefficiently to get more carbon credits. But such rules could also shortchange older, inherently more polluting coal plants.

There is also the issue of volatility with voluntary carbon space. Although the market has grown beyond US$2 billion, it has been facing a year-long slump due to macroeconomic headwinds and major integrity allegations.

Yvonne Lam, a senior vice-president and head of research in carbon and carbon capture at Norway-based research firm Rystad Energy, said adding carbon credits to a coal retirement financing package could therefore make things more complicated. There is also a “backlash” about the quality of carbon credits, Lam noted.

Lam said it could be more feasible today to decarbonise coal plants using carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies instead of trying to retire them early, since this would bypass having to build new power capacity and compete against existing long-term power contracts.

Interest in CCUS has been steadily growing among energy majors in Asia, though sceptics say such technology is nascent, expensive and extends the lifespan of fossil fuels.

“CCUS will probably be more [useful in the] short-term, while planning for the long-term where [coal plants] are replaced with renewables,” Lam said, adding that carbon capture technology has already been proven.

If coal phaseout does become a form of carbon removal project, it could also inflate risks should emissions savings be double-counted, and overstated, by different entities – given the millions of carbon credits likely involved.

Currently, nothing prevents double counting between a business working towards their voluntary net-zero goal, and countries fulfilling decarbonisation obligations, known as “Nationally Determined Contributions” (NDCs) under the global Paris Agreement climate treaty.

“The argument is that [voluntary] carbon markets are often too small to affect how countries think about their NDCs. But if you’re now shutting down coal-fired power plants, it isn’t small anymore. This is going to show up in the national inventory and you cannot argue that this double-count is irrelevant,” Hewlett said.

Rystad’s Lam noted that such rules around country-level carbon trading have been slow to finalise, and there could be updates by COP28, the next climate negotiations in Dubai in November.

More details around coal phaseout project methodologies could be ready around then too. Curtin said CCCI will not be certifying projects, but will work with an existing major carbon credit certifier.

The partner is likely not Gold Standard. Hewlett says the certifier has tried to keep itself “at arm’s length” from other initiatives. Consolidation into a single effort may not be a good thing, in case the sole initiative goes wrong, Hewlett explained.

Other big carbon registries worldwide include US nonprofits Verra, Carbon Action Reserve and American Carbon Registry.

Curtin said CCCI considers coal phaseout projects a “premium product” for the “very high end” of the carbon market. The initiative is envisioned to be a gigatonne-level solution that closes dozens of coal plants, though it intends to start with one in Indonesia.

Meanwhile, Hewlett said there may be opportunities in helping smaller jurisdictions transition from coal to clean energy before they “go too deep in the direction of fossil fuels”.

Both Gold Standard and CCCI say they will want developers to focus on protecting affected communities – such as those who may lose jobs or power. Sari of Landscape Indonesia noted that coal miners, and not just power plant workers, should be accounted for too. There are about 250,000 workers in Indonesia’s coal mining sector alone.

“It is amazing how simple a concept can look, but when you get into each individual line, there is a lot to think about. Nothing is simple,” Hewlett said.